You have a goal. You consider how to reach it. There seems to be a clear path to it. You define action steps. You go for it…

Many of us chose this approach as we pursue goals. It seems obvious enough, yet we make a big assumption. The assumption is that the direct path is the shortest (or best) path.

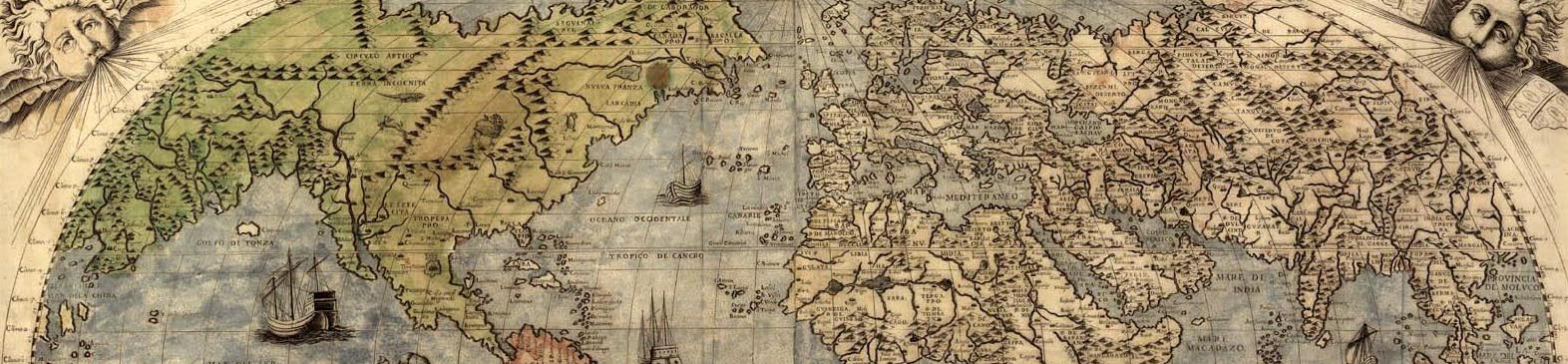

Many of you know that I enjoy sailing. Like in other outdoor activities, maps are used to help you get from point A to point B. The standard type of chart is a so-called Mercator projection. It’s a specific way to take actual land and sea contours from the globe and represent it on a flat map. If you ever tried to flatten a deflated soccer ball, you know that you won’t be able to get it flat. It leaves wrinkles; you have to compress and stretch it in places. On a map, it leads to distortions

On a Mercator map, the way it’s done preserves angles and not distances. It sounds a bit technical, but the great benefit is that you can plot a course on the map, determine the heading (angle to North) and maintain that angle to North (i.e., your compass reading) as you head towards the destination. (Side remark for the geometry fans: on a globe, this doesn’t work. The angle to North changes as you approach your destination in a straight line.)

One of the quirks to a Mercator map is that a straight line is not the shortest distance. For short sailing turns on the Chesapeake Bay, this doesn’t matter much because the difference is small. Yet on a long trip, this matters a lot. Following a straight line as you sail from Florida to France will add hundreds of miles and several days to the trip.

The shortest distance between A and B on a Mercator map is a curve. You may have seen it on a long flight on the in-flight map.

The same is often true in life and work. The shortest path is curved.

The mental map we have of the world is also a projection. It’s a projection of reality onto how our mind understands and grasps reality. Have you ever discovered that what you thought to be so, actually, wasn’t so? That’s one of the distortions created by your mental map.

Consider that what you see as the direct path is not the shortest path. How do you get on the shortest path?

Maybe it’s an additional conversation with a stakeholder. Perhaps it’s one more meeting to get more buy-in from the team. Maybe it’s further research to dispel something that’s in the back of your mind. Maybe it’s saying “no” to something that seems to pull us on what appears to be the direct way.

How do you know if any particular step is the right step? You try it out. Take a small action and assess if you’re closer to the destination. As you practice this, you’ll get better at understanding what the shortest route really is – and how your mental map projects the real world.

Take the next step

Take a look at your action list for a medium or long term goal. Think of possible actions that are close to what you’ve considered as an action path. Decide on a couple of ‘nearby’ action items and add them to your action list. Execute these seemingly non-direct actions and see where it takes you.